A friend messaged me late last night with the scary news that Google had emailed him about a ton of spammy subdomains on his own domain.

Any idea how this could have happened, he asked?

Security is not my bag, but I do like poking around things to understand how they tick, and this particular exploit kinda intrigued me by its simplicity. I’m a big advocate of running your own blog, but the downside is you also own some (PaaS) or all (IaaS) of the security. Here’s an example where things can slip if you’re not careful.

A Quick Primer on GitHub Pages 🔗

GitHub Pages give you the very nice ability to host a static site for free. Dump some HTML into a GitHub repository, tell GitHub to activate it for GitHub Pages, and off you go!

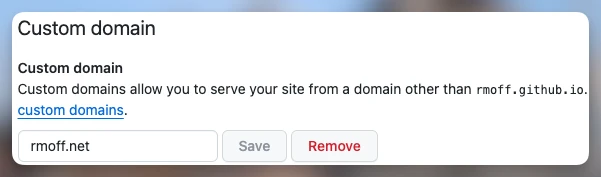

What’s more, you can use a custom domain. So instead of your_user.github.io you can send users to fancy-website.com.

GitHub Pages Is One Set Of Servers Serving Many Websites Not Just Yours 🔗

When you breathlessly type in rmoff.net to your browser to read my latest ramblings it’s not going to a dedicated IP address. It’s going to the GitHub Pages web server farm, which sees the request for rmoff.net and happily serves up the requested content.

How does your browser know to ask GitHub Pages for rmoff.net? DNS.

❯ nslookup rmoff.net

Server: 192.168.10.1

Address: 192.168.10.1#53

Non-authoritative answer:

Name: rmoff.net

Address: 185.199.108.153That 185.199.108.153 is an IP address for GitHub Pages' servers, and it’s where your browser will fetch the actual content from.

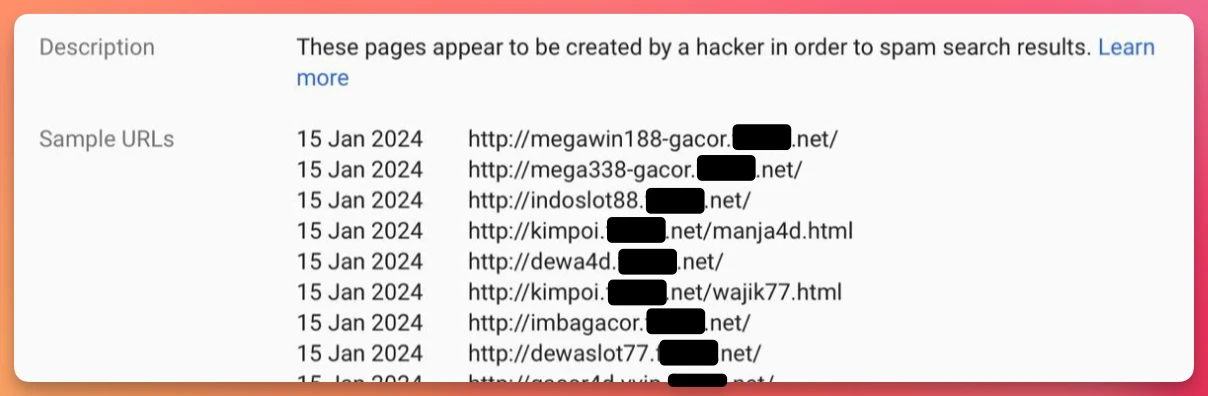

Here’s the Hijack 🔗

Let’s look at a real example, using another of my domains—rmoff.info.

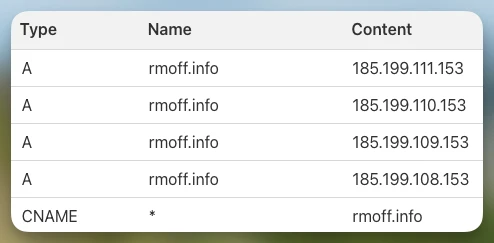

Part 1 - DNS CNAME Wildcard 🔗

Here’s a seemingly-innocuous (to the untrained eye, i.e. me) set of DNS records for rmoff.info:

The brace of IP addresses is the servers from which GitHub Pages is serving the rmoff.info site.

| If you’re eagle-eyed you might notice that the list here includes the IP address that we saw above, which is for a different domain. That’s by design and key to this issue. |

So if I lookup the IP address for rmoff.info, as expected I get back this set of IPs for GitHub Pages:

❯ dig +short moff.info

185.199.108.153

185.199.111.153

185.199.110.153

185.199.109.153What about a random subdomain?

❯ dig +short spammy-crap.rmoff.info

rmoff.info.

185.199.108.153

185.199.111.153

185.199.110.153

185.199.109.153Huh - turns out I also get the IP addresses for the GitHub Pages servers.

Herein lies the first part of the problem. The wildcard CNAME entry will match any subdomain and redirect it to rmoff.info (known as the "apex", or root). This in turn is configured as we saw above to point to the GitHub Pages addresses. And thus any request for a subdomain will be directed to GitHub Pages' servers.

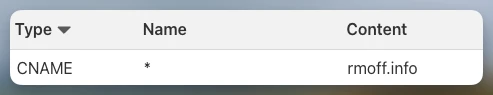

Part 2 - GitHub Pages Is Not Fussy 🔗

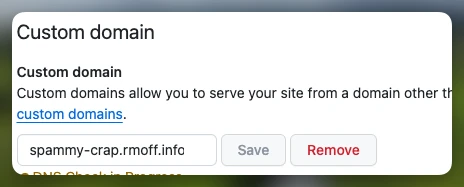

When I create the CNAME for my blog on GitHub Pages I can put anything there. Same with the custom domain configuration in GitHub Pages settings:

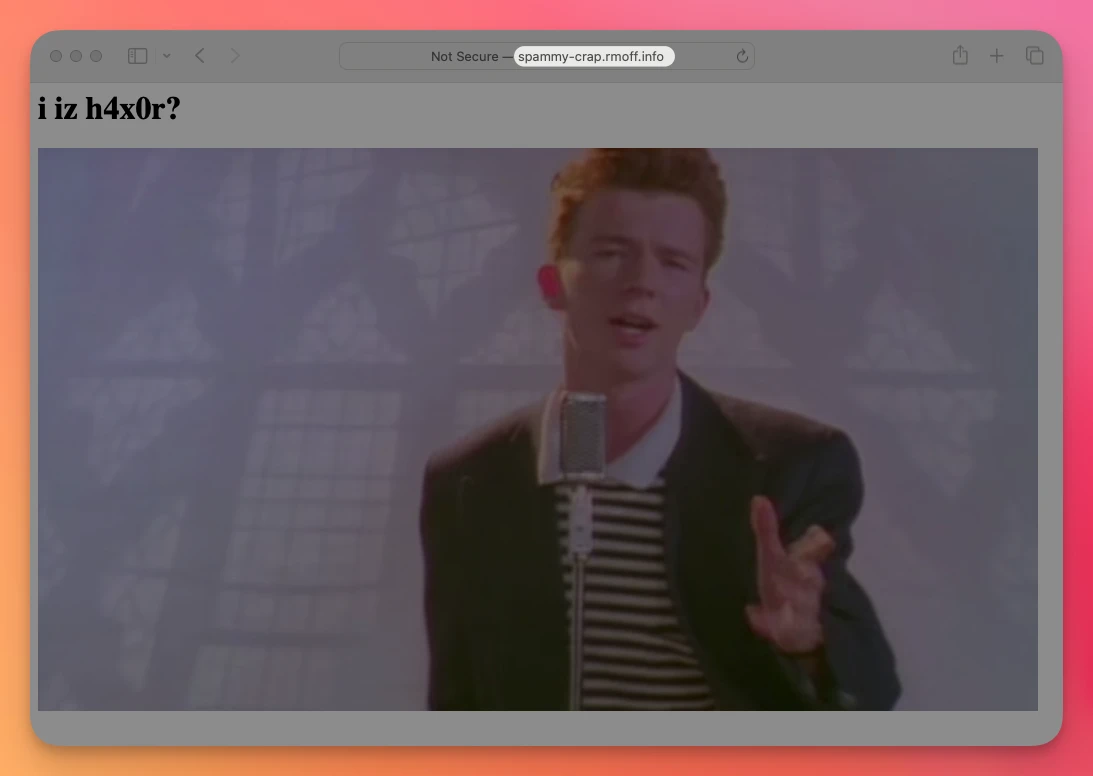

All this does is tell the GitHub Pages web servers that this content here is for the domain I tell it. If I decide to put in a domain that I don’t own but want to use for nefarious purposes, I can do so. So let’s say I am a h4x0r and want to pwn some subdomains on rmoff.info. I spin up a GitHub pages repo and put in spammy-crap.rmoff.info as the custom domain.

I own rmoff.info so it’s up to me what I do with it, but I’m pretty sure doing this on someone else’s domain with this DNS mis-configuration is gonna be illegal and if not Just Wrong, so don’t.

|

This means that anyone who hits the GitHub Pages web servers (which we’ve seen above is fronted by that block of four IP addresses) asking for spammy-crap.rmoff.info is going to get served the contents of the repository that I created.

Let’s try it out and go click on 🔗 spammy-crap.rmoff.info

Connecting the Dots 🔗

So GitHub Pages can be tricked into serving content for a domain that I don’t own. So what? Who is ever going to find that URL?

The next step in the hijacking attack is presumably to try and get Google to index these spam sites (hence the alert that went to my friend), or link to them from other sites, or whatever. The point is, once the URL is out there, it’s in the wild.

Now you, as the owner of the domain, appear to be hosting spam sites, bots, and who-knows-what-else.

tl;dr: Be very careful with wildcards in DNS records 🔗

If you have a wildcard DNS entry, make sure you know 💯 why it’s there. If not, you are leaving yourself wide open to this kind of hijacking of your subdomains. The reputational damage of spammers and ne’er-do-wells besmirching the good name of your domain is not worth it, whether in the eyes of actual visitors who somehow end up on the page, or Google et al who will see this kind of domain abuse as a reason to downgrade your domain itself. Because scammers won’t just create a simple rick-roll—they’ll create many dozens of subdomains, serving all sorts of botnets, phishing sites, and general crap.

And to recap, all that I needed to do to hijack subdomains was:

-

Find a domain with a wildcard in the apex DNS entry (in this case, my own for demonstration purposes).

-

Create a GitHub Pages repository with its custom domain name configured to a subdomain within this domain.

-

That’s it!

| My thanks to Oliver Hookins for his rapid help in diagnosing and explaining this issue. |

I have, obviously, removed the wildcard DNS record from rmoff.info before publishing this, so don’t even try 😝

I left in place an A record just for spammy-crap so that you can see the domain→GitHub Pages resolution in practice.