In this article I look at where we store our analytical data, how we organise it, and how we enable access to it. I’m considering here potentially large volumes of data for access throughout an organisation. I’m not looking at data stores that are used for specific purposes (caches, low-latency analytics, graph etc).

The article is part of a series in which I explore the world of data engineering in 2022 and how it has changed from when I started my career in data warehousing 20+ years ago. Read the introduction for more context and background.

Storing and Accessing Your Data pt 1: 🔥 Burn It All Down…🔥 🔗

In the beginning was the word, and the word was an expensive relational datawarehouse that wasn’t flexible or scalable enough for the cool kids in Silicon Valley.

Then came Hadoop and scalability was won, at the vast cost of usability. You literally had to write your own Java code to move data around and transform it. You needed to serialise and deserialise the data yourself, and could store whatever you wanted - it didn’t have to be structured. This was sold as a benefit — "Schema on Read" they said, "It’ll be a good idea", they said. "Oh bugger, where’s my schema", they said when they came to use it.

Through the virtues of open source a fantastic ecosystem grew particularly around the Apache Software Foundation and we got such wonderfully named projects as Sqoop, Oozie, Pig, and Flume emerged. Hive brought with it the familiar and comforting bosom of SQL and table structures but with limited functionality (including no DELETE or UPDATE at first) and performance.

Over the years things improved, with Spark replacing MapReduce and enabling a generation of Python coders to get into the big data lark too, along with SQL.

Amongst all of this pioneering work and technology was the assumption that the resting place for analytical data was HDFS. Other stores like HBase existed for special purposes, but the general we’ve-got-a-bunch-of-data-in-this-org-and-need-to-collect-it destination was HDFS. Because "general dumping ground" wasn’t sexy enough for the marketing folk it became sold as a "Data Lake" with all the associated puns and awful cliches (fishing for data, data swamp, etc etc etc).

The general pitch around the data lake was to collect all the data, structured and unstructured (or structured that you’ve made unstructured by chucking away its schema when you loaded it), and then wait for the data lake fairy to conjure magical value out of the pile of data you’ve dumped there make the raw data available for teams in the company to process and use for their particular purposes. This may have been direct querying of the data in place, or processing it and landing it in another data store for serving (for example, aggregated and structured for optimal query access in an RDBMS or columnar data store).

Accessing the data in HDFS was done with Hive and other tools including Impala, Drill, and Presto. All had their pros and cons particularly in early releases, often with limitations around performance and management of the data.

All of this was built around the closely-intertwined Hadoop platform, whether self-managed on-premises including with deployments from Cloudera, MapR, and Hortonworks, or with a cloud provider such as AWS and its EMR service.

This was pretty much the state of the Big Data world (as it was called then) as I last saw it before getting distracted by the world of stream processing - fragmented, more difficult to use, less functionality than an RDBMS for analytics, and evolving rapidly.

Storing and Accessing Your Data pt 2: …and Then Rebuild It 🏗️ 🔗

Coming back to this after my attention being elsewhere for a few years means that I have the slightly uninformed but helpfully simplistic view of things. What the relational data warehouses used to do (bar scale, arguably), we are now approaching something roughly like parity again with a stack of tools that have stabilised and matured in large, with a layer on top that’s still being figured out.

Underpinning it all is the core idea of separation of storage and compute. Instead of one box (the traditional RDBMS), we have two. This is important for two vital reasons:

-

It’s a lot cheaper to just store data and then only pay for compute when you want to use it.

The alternative is that you couple the two together which is what we’ve generally always done and is seen in every RDBMS, like Oracle, DB2, etc etc. With the coupled approach you have a server with disks and CPUs and you’re paying for the CPUs whether they’re doing anything or not, and when you need more storage and have filled the disk bays you need to buy (and license, hi Oracle) another server (with CPUs etc).

The added element here is that you have to provision your capacity for your peak workload, which means over-provisioning and capacity sat idle potentially for much of the time depending on your business and data workload patterns.

-

If your data is held in an open format on a storage platform that has open APIs then multiple tools can use it as they want to.

Contrast this to putting your data in SQL Server (not to pick on Oracle all the time), and any tool that wants to use it has to do so through SQL Server. If a new tool comes along that does particular processing really really well and your data is sat in an RDBMS then you have to migrate that data off the RDBMS first, or query it in place.

Given the Cambrian explosion that’s been happening in the world of software and showing no signs of abating, setting ourselves up for compatibilty and future evolution of software choices seems like the smart move.

HDFS and Hive gave us this separation, right? Well, it did, but with a long list of problems and limitations for Hive. These include poor perfomance, a lack of support for transactions, point-in-time querying, streaming updates, and more. In addition, HDFS has nowadays been overtaken by S3 as the object store of choice with APIs supported by numerous non-S3 platforms, both Cloud based (e.g. Google’s Cloud Storage (GCS), and Cloudflare’s R2) and on-premises (e.g. Minio).

So if it’s not HDFS and Hive, what’s the current state and future of analytics data storage & access looking like?

Data Lake Table Formats & Data Lakehouses 🔗

So, full disclosure first:

😳Confession: Until last week I honestly thought "data lakehouse" was some god-awful marketing bollocks and nothing more.

— Robin Moffatt 🍻🏃🥓 (@rmoff) September 2, 2022

🙈Embarrassed to find out there's actually a rather interesting paper from last year describing the concept in detail: https://t.co/XEI0zGSXBl

You can read the Lakehouse paper (and more detailed one) and decide for yourself its virtues, but I found it a useful description of a pattern that several technologies are adopting, not just Databricks and their Delta Lake implementation of the Lakehouse. I’ll admit, the name grates—and I miss the Hadoop days of fun names 😉.

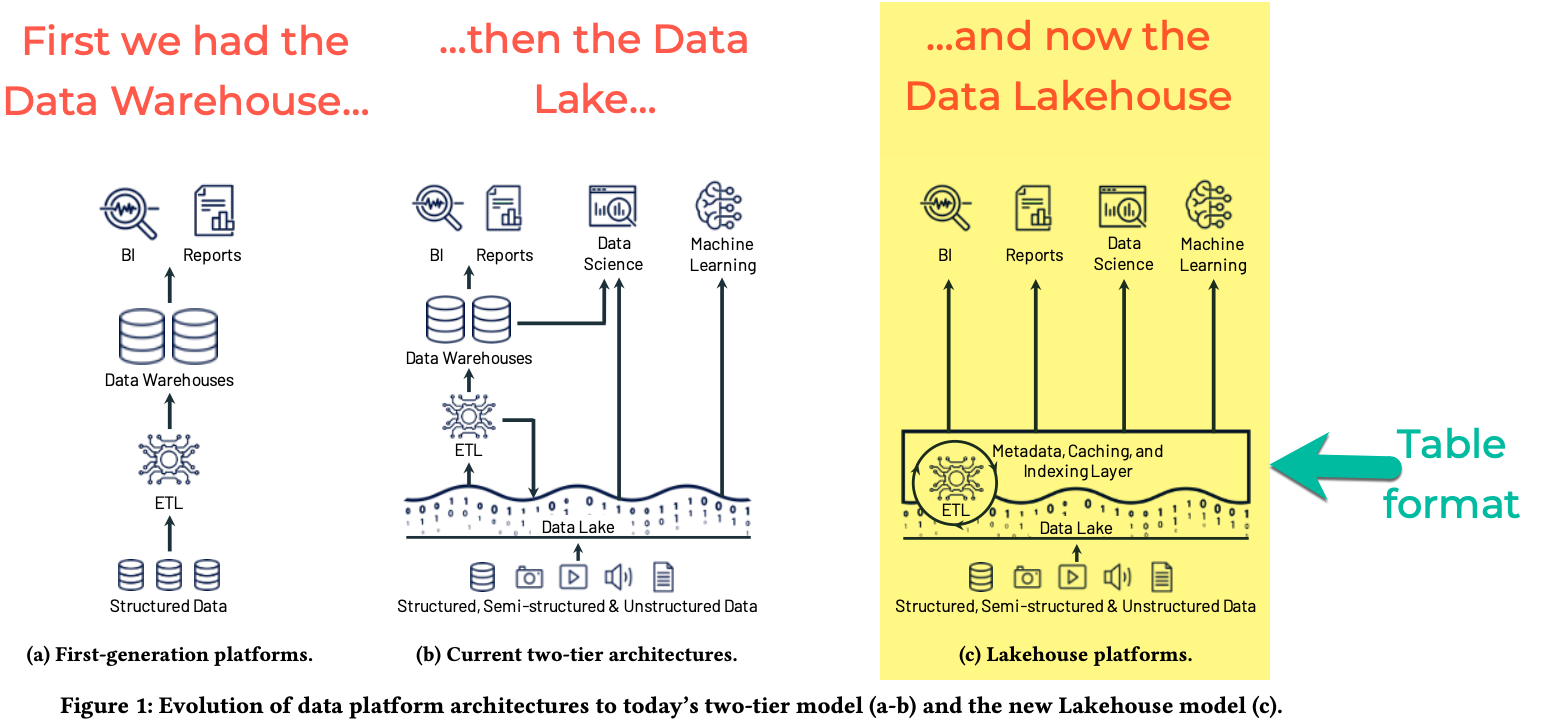

In short, the "Lakehouse" concept is where data is stored on object store (the Data Lake) with a layer above it providing a "table format" through which data can be read and written in a structured way, supporting updates and deletes to the data, as well as queried in an efficient way. The Lakehouse is the whole; the table format is the specific layer of technology that implements the access on the data in your Data Lake.

Whether you go for the Lakehouse term (Databricks would like you to, and Snowflake are onboard too, and maybe even Oracle) or just the Data Lake plus Table Format, it’s a really interesting idea. The bit that really catches my attention is that it enables a common table structure to be defined and accessed by a variety of compute engines - meaning that in both querying and processing (ETL/ELT) the data can be structured and manipulated in the way in which you would in an RDBMS.

There are three table formats available:

All of them enable the things that we’d have taken for granted a decade ago including rich metadata, transactional access, `UPDATE`s, `DELETE`s, and ACID compliance, along with performant access when querying the data.

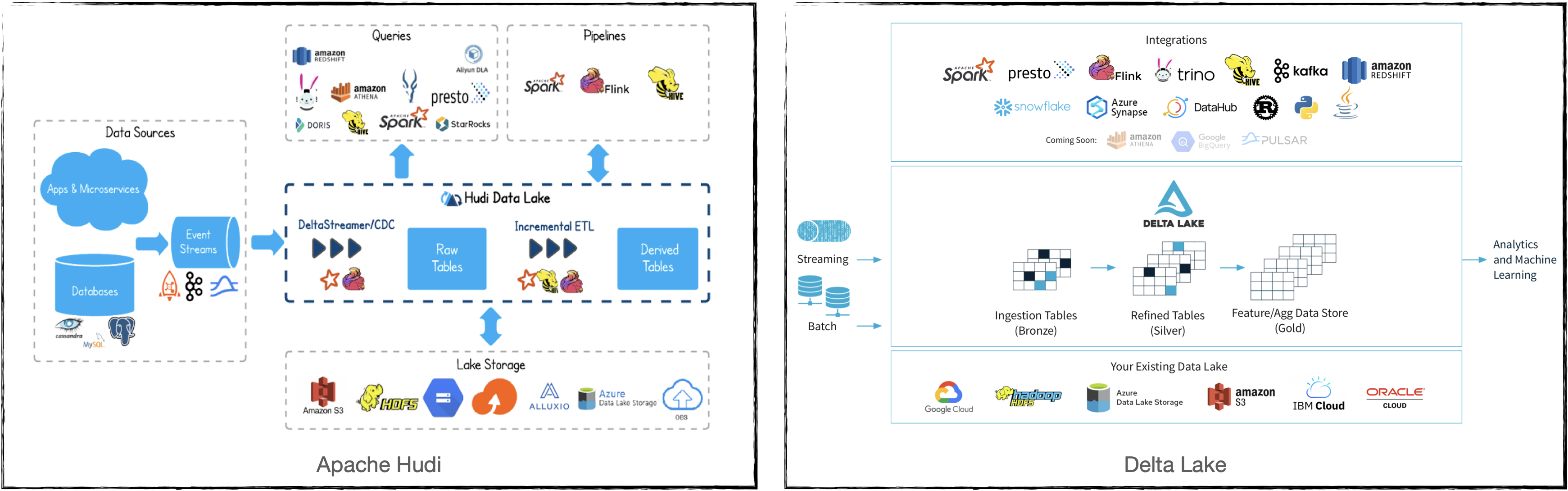

Both Hudi and Delta Lake have a similar conceptual diagram which illustrates things well. Note the plethora of query engines and integrations that each support.

(image credits: Apache Hudi / Delta Lake)

Managed Data Lakehouses 🔗

You can run run your own, or use used hosted versions including

-

Onehouse (Apache Hudi)

-

Tabular (Apache Iceberg)

-

Databricks (Delta Lake)

-

GCP's BigLake (Iceberg?)

Azure have a close partnership with Databricks, so the only major cloud provider missing from this list is AWS. They have Lake Formation and Governed Tables which looks similar on the surface but I’ve not dug into in detail (and Governed Tables aren’t even mentioned on AWS' Build a Lakehouse Architecture on AWS blog).

Snowflake recently added support for Iceberg tables (complementing the existing support for Delta Lake external tables), and are backing Iceberg — presumably in part to try and hamper Databricks' Delta Lake (see also their snarky comments about "Iceberg includes features that are paid in other table formats", "The Iceberg project is well-run open source" etc, taking a shot at the fact that Delta Lake has paid options, and the majority of committers are from Databricks).

Dremio are also in this space as one of the companies working on Apache Arrow and providing a fast query engine built on it called Dremio Sonar. I’ve yet to get my head around their offering, but it looks like on-premises platform as well as hosted, with support for Apache Iceberg and Delta Lake. They’ve got a rich set of resources in their Subsurface resource area.

Oracle being Oracle are not ones to miss up the chance to jump on a buzzword or marketing bandwagon. Their version of the Lakehouse however looks to be to stick their Autonomous Data Warehouse (it’s self driving! self healing!) on top of a data lake - kinda like Snowflake have done, but without the open table format support of Apache Iceberg. The huge downside to this is that without the open table format there’s zero interoperability with other query & processing engines - something Oracle are presumably not in a rush to enable.

Storage Formats 🔗

Regardless of which table format you implement, you still store your data in a format appropriate for its use - and that format is separate from the table format (confused yet? you might be). Different table formats support different storage formats but in general you’ll see various open formats used:

Regardless of the format, the data is stored on storage with an open API (or at least one which is widely supported by most tools) - S3 becomes the de facto choice here.

Reading more about Table Formats & Lakehouses 🔗

Here are some good explanations, deep-dives, and comparison posts covering the three formats:

-

An Introduction to Modern Data Lake Storage Layers - Damon Cortesi (AWS)

-

Comparison of Data Lake Table Formats blog / video - Alex Merced (Dremio)

-

Apache Hudi vs Delta Lake vs Apache Iceberg - Lakehouse Feature Comparison - Kyle Weller (Onehouse)

-

Hudi, Iceberg and Delta Lake: Data Lake Table Formats Compared - Paul Singman (LakeFS)

A Note About Open Formats 🔗

Whether we’re talking data lakes, Lakehouses, or other ways of storing data, open formats are important. A closed-format vendor will tell you that it’s just the "vendor lockin bogeyman man" pitch and how often do you re-platform anyway. I would reframe it away from this and suggest that just as with tools such as Apache Kafka, an open format enables you to keep your data in a neutral place, accessible by many different tools and technologies. Why do so many support it? Because it’s open!

In a technology landscape which has not stopped moving at this pace for several years now and probably won’t for many more, the alternative to an open format is betting big on a closed platform and hoping that nothing better comes along in the envisaged lifetime of the data platform. Open formats give you the flexibility to hedge your bets, to evaluate newer tools and technologies as they come along, and to not be beholden to a particular vendor or technology if it falls behind what you need.

In previous times the use of an open format may have been moot given the dearth of alternatives when it came to processing the data—never mind the fact that the storage of data was usually coupled to the compute making it even more irrelevant. Nowadays there are multiple "big hitters" in each processing category with a dozen other options nibbling at their feet. Using a open format gives you the freedom to trial whichever ones you want to.

Just a tip to vendors: that’s great if you’re embracing open formats, but check your hubris if you start to brag about it whilst simultaneously throwing FUD at open source. Just sayin'.

git For Data with LakeFS 🔗

Leaving aside table formats and lakehouses for the moment—and coming back to the big picture of how we store and access data nowadays—one idea that’s caught my attention is that of being able to apply git-like semantics to the data itself. Here’s a copy of a recent Twitter thread that I wrote.

Having watched @gwenshap and @ozkatz100 talk about "git for data" I would definitely say is a serious idea. However to the point at the end of the video, RTFM—it took reading page from the docs and some other pages subsequently to really grok the concept in practice.

Where I struggled at first with the git analogy alone was that data changes, and I couldn’t see how branch/merge fitted into that outside of the idea of branching for throwaway testing alone. The 1PB accidental deletion example was useful for illustrating the latter point for sure.

But then reading this page made me realise that I was thinking about the whole thing from a streaming PoV—when actually the idea of running a batch against a branch with a hook to validate and then merge is a freakin awesome idea

(As the roadmap issue notes, doing this for streaming data is conceptually possible but more complex to implement.)

I’m also still trying to think through the implications of merging one branch into another in which there are changes; can data really be treated the same as code in that sense, or could one end up with inconsistent data sets?

Lastly, having been reading up on table formats, I’d be interested to dig into quite how much LakeFS works already with them vs roadmap alone (the docs are not entirely consistent on this point)—but with both in place it sounds like a fantastic place for data eng to be heading.

The "git for data" pitch is a great way to articulate things, but it also shifted my brain off some of the central uses. For code, git is an integral part of the development process but once it hits Production git steps back from an active role. However, in the case of LakeFS some of their most exciting use cases are as part of the Production data process. The docs have several examples which I think are just great:

-

When your batch pipeline runs, it does so against a branch of the data. Before merging that branch back into trunk, a hook can be configured to do various data quality checks (just as you’d configure hooks in GitHub etc to check for code quality, test suites, etc etc). This could be things like checking for PII slipping through, or simply "did we process the approximate number of records that we would expect". If that kind of check fails because the source data’s gone bad or failed up stream then you potentially save yourself a ton of unpicking that you’d have to do if it’s updated directly in the Production data lake.

-

As above, the batch pipeline creates a new branch when it runs, and when (or if) it completes successfully and merges that back into the trunk, that merge can have attached to it a bunch of metadata to do with the pipeline execution. What version of the code was it running, what version of the underlying frameworks on which it executed, and so on. Invaluable for tracing particular problems at a later date.

I kicked the tyres on LakeFS and wrote about it here

Data Engineering in 2022 🔗

-

Query & Transformation Engines [TODO]